- Many scientists argue that the planet seems to be undergoing a sixth mass extinction, with global fauna experiencing a major collapse in numbers.

- The five previous mass extinctions were caused by catastrophic events like asteroid collisions. This time, human activities are to blame.

- Deforestation, mining, and carbon dioxide-emissions, which cause the Earth to warm, are driving species around the world to extinction.

- A new study shows that the last time the planet experienced a mass extinction – which wiped out the dinosaurs – it took Earth’s species 10 million years to recover.

Some 65 million years ago, an asteroid just six miles wide struck the planet. The resulting cloud of dust and debris that funneled into the atmosphere blocked sunlight for several weeks, while earthquakes, landslides, and tsunamis wreaked havoc on what is now the Americas.

When all was said and done, the Tyrannosaurus rex and its Saurichian compatriots had all died out, along with 75% of the planet’s species.

Today, another force is driving Earth towards its next extinction event. Human-driven changes to the planet are hitting global species on multiple fronts, as hotter oceans, deforestation, and climate change drive floral and faunal populations to extinction in unprecedented numbers. As much as half of the total number of animal individuals that once shared the Earth with humans are already gone, a clear sign that we’re on the brink, if not in the midst of, a sixth mass extinction.

Read more: 12 signs we’re in the middle of a 6th mass extinction

A new study published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution reveals that it took the planet around 10 million years to recover from the mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs.

That's bad news if we want to get Earth's currently dipping biodiversity back on track.

"From this study, it's reasonable to infer that it's going to take an extremely long time - millions of years - to recovery from the extinction that we're causing through climate change and other methods," co-author of the new study Andrew Fraass said in a press release.

As we continue to encroach on animals' habitats, pollute their ecosystems, and drive the Earth towards warmer and warmer temperatures, we're stubbornly marching away from a version of the world that we will never be able to get back.

"Biodiversity losses won't be replaced for millions of years, and so when you imagine extinctions in coral reef ecosystems, or rain forest ecosystems, or grasslands, or wherever, those places are going to be less diverse essentially forever, as far as humans are concerned," Chris Lowery, paleobiologist and co-author of the new study, told Business Insider.

An evolutionary 'speed limit'

Scientists have long argued that the 10-million-year time frame for global biodiversity to properly rebound is a feature of all five of Earth's mass extinctions, but for the first time, there's now fossil evidence of that delay.

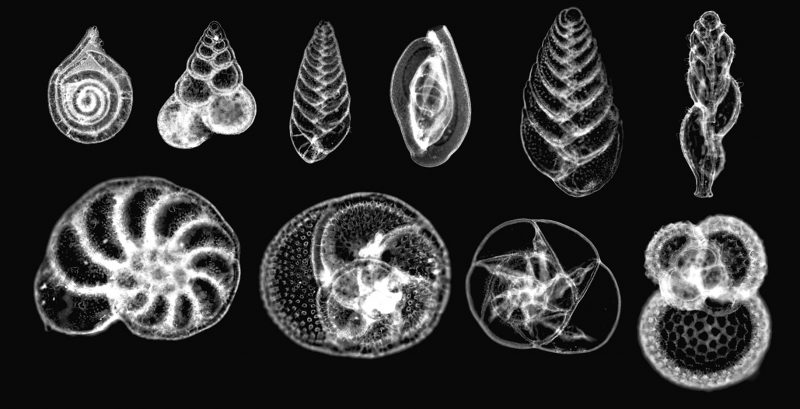

In order to determine how quickly Earth's biodiversity recovered after the mass extinction event 65 million years ago, Lowery and Fraass examined tiny single-celled organisms called planktic foraminifera that are abundant in the fossil record (there are some 4,000 species still alive today, according to the University of California Museum of Paleontology at Berkeley).

The paleobiologists looked at how foraminifera biodiversity changed in the fossil record from before the extinction event to after, and how long it took for the organism's level of biodiversity to return to pre-asteroid levels after the catastrophe.

In an ecosystem, each animal and plant species occupies a unique niche - the specific part of an ecosystem that an organism inhabits. Following a mass disappearance of species, one might think that these niches would still be available for adaptable extinction survivors to then take over. But according to Lowery, that's not the case.

"Niches and the organisms that fill them are basically inseparable, so a mass extinction destroys niches as it destroys species," he said. The new study shows that these complex ecological niches need to be rebuilt before species diversity can fully recover, and that's the reason behind the delay.

The authors discovered that the surviving foraminifera species got more complex (and thus able to create and fill new niches) before they diversified, suggesting ecological complexity precedes diversification.

"What's interesting is that there seems to basically be a hard speed limit for this process, and it takes about 10 million years to complete," Lowery added.

The study authors wrote that the generation of new ecological niches following a mass extinction means that the world that re-populated after the asteroid strike was a "wholly new" ecosystem, "rather than a return to a mirror version" of the what the world was like before the extinction.

"This should serve as an important reminder: some ecological niches lost due to anthropogenic climate change will never reappear," they wrote in the study.

There's consensus on one aspect of the extinction trend: it's all our fault

"It's astounding to me that humans have the capacity to influence the earth system, in this case the biosphere, on truly geologic timescales," Lowery said. "I think this really underscores how important conservation is."

Scientists are still arguing about whether the Earth is truly in the midst of another mass extinction.

Lowery doesn't think we've strayed into Sixth Extinction territory yet. But he and Fraass agree that squabbling over what constitutes that distinction is besides the point.

"We have to work to save biodiversity before it's gone. That's the important takeaway here," Lowery said.

There is consensus on one aspect of the extinction trend, however: Homo sapiens are to blame. According to a 2014 study, current extinction rates are 1,000 times higher than they would be if humans weren't around.

"It's incredible that humans have the capacity to damage the biosphere so severely that it will take millions of years to recover," Lowery said.